Table of Contents

The Myth of the Dancing Horse: Spectacle vs. Sentience. There’s a term that floats around equestrian circles and beyond: “dancing horses.” To the untrained eye, it evokes elegance, artistry, and joy. But behind the choreography lies a troubling truth - one that deserves to be seen, named, and challenged.

I can't tell you how many times, when I have tried to explain the training I do to a non-horsey person, they say "ooh I love dressage, the horses really look like they are dancing - the commentator said the horse was loving the music, they look so happy!". Or, as happened to me this weekend, "my family love horses - my brother bought a dancing horse - he paid £2,000 for it!".

Cultural Spectacle: The “Dancing Horse”

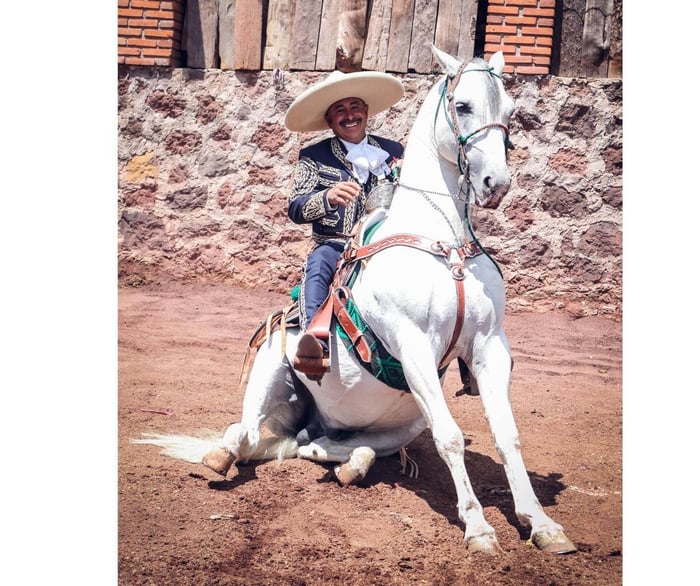

In many countries, including India, Pakistan, Rajasthan, and Mexico, horses are trained to perform exaggerated, unnatural movements at weddings and festivals. These displays - often called “dancing” - involve high-stepping, head tossing, and rhythmic footwork that mimic human dance. But the reality is far from joyful.

These horses are frequently trained using cruel methods: pain-based conditioning, tight restraints, and relentless repetition. Their bodies are contorted into postures that strain joints, compress the spine, and disrupt natural movement. What looks like celebration is often suffering in disguise.

The term “dancing horse” in this context is a euphemism for exploitation. It’s a spectacle built on submission, not partnership.

Horses are not designed to sit in this way, especially with a heavy rider and saddle on board. An example of showmanship taking priority over wellfare. I will spare you the actual images of dancing horses - a web search will provide if you are curious.

Horses are not designed to sit in this way, especially with a heavy rider and saddle on board. An example of showmanship taking priority over wellfare. I will spare you the actual images of dancing horses - a web search will provide if you are curious.Competitive Dressage: A Misguided Parallel

In Western contexts, the phrase “dancing horse” is often applied to competition dressage. While the intent may differ, the outcome can be disturbingly similar. Horses are taught to perform precise movements—piaffe, passage, pirouette—often under pressure and with an emphasis on visual perfection.

The problem isn’t the exercises themselves. It’s how they’re taught and why. When training prioritises aesthetics over biomechanics, horses are forced into postures that may look impressive but are unnatural. Overbent necks, hollow backs, and tension through the body are common signs of discomfort masked as elegance.

Even when movements appear to match the music, it’s not because the horse is “dancing.” It’s because the rider is influencing the rhythm through bodyweight, aids and timing. The horse is responding, not expressing.

This is the norm for high level competition dressage. The horse has his weight on his fragile front legs, and the hind legs are pushing back and out. The rider is pulling the horse's nose in which shortens his neck and causes the centre of mass to shift even more towards the front legs. The spurs dig in to try to solve the problem by activating the hind legs but it won't help because it's impossible for the horse to do anything different. The result is a hollow back, stressed tense horse, and too much froth coming out of the horse's mouth where he is struggling to swallow.

This is the norm for high level competition dressage. The horse has his weight on his fragile front legs, and the hind legs are pushing back and out. The rider is pulling the horse's nose in which shortens his neck and causes the centre of mass to shift even more towards the front legs. The spurs dig in to try to solve the problem by activating the hind legs but it won't help because it's impossible for the horse to do anything different. The result is a hollow back, stressed tense horse, and too much froth coming out of the horse's mouth where he is struggling to swallow. Misreading the Horse: The Danger of Assumptions

Spectators often interpret these displays as signs of happiness or pride. But horses don’t smile. They don’t dance for applause. What we see as beauty may be:

- Learned helplessness—a psychological state where the horse stops resisting because resistance has proven futile

- Suppressed pain responses—stoicism mistaken for serenity

- Conditioned compliance—obedience mistaken for joy

Without understanding equine biomechanics, emotional signals, and natural movement, it’s easy to mistake suffering for spectacle.

The horse cannot escape the bit because of a tight noseband and flash. He can't swallow because his nose is drawn in behind the vertical by pressure on his mouth, his nostrils flare and his eye shows distress, his entire demeanour shows helplessness and despair.

The horse cannot escape the bit because of a tight noseband and flash. He can't swallow because his nose is drawn in behind the vertical by pressure on his mouth, his nostrils flare and his eye shows distress, his entire demeanour shows helplessness and despair. Movement with Meaning: A Different Path

At Balance First, also in Straightness Training and the Academic Art of Riding, we teach dressage exercises that may look similar to competition dressage, and have the same names, but the purpose is radically different. Our work is rooted in:

- Biomechanical integrity: Supporting the horse’s natural asymmetry and physical development

- Emotional well-being: Encouraging relaxation, curiosity, and choice

- Mental enrichment: Building trust, understanding, and mutual respect

We don’t train horses to perform. We guide them to move in a healthy way that feels good, and supports their physical, mental and emotional wellbeing. The goal isn’t applause - it’s good health. Not just of limbs, but of purpose, philosophy, and heart.

Almost any rider or trainer can train in this way with their horse. It just means taking a different approach, changing your priorities, for the horse's sake.

The collected movements like piaffe, passage, and levade are entirely natural for the horse, and they will perform them spontaneously in freedom, but only for a very short length of time (it's hard work) and out of high spirits.

It can be trained, of course, but should be done in a way that enhances nature without corrupting it, and that preserves the spirit and physical and mental well-being of the horse.

It is not healthy for horses to repeat collected movements for long periods of time, or to be tied down and operated like a puppet.  A horse in natural self-carriage. The horse moves uninhibited, his haunches bend and hind legs are strong and step forward and under to support his body weight. His toplne is long, his nose is in front of the vertical and his under neck muscles are loose and soft. His front legs are light and shoulders free. His spirit shows through and whole demeanour is natural, contented and free.

A horse in natural self-carriage. The horse moves uninhibited, his haunches bend and hind legs are strong and step forward and under to support his body weight. His toplne is long, his nose is in front of the vertical and his under neck muscles are loose and soft. His front legs are light and shoulders free. His spirit shows through and whole demeanour is natural, contented and free. An arab looking contented in natural self-carriage. His under neck is soft, his shoulders are enlightented. His tail is high and his topline slightly shortened but that is in the breeding of the Arab.

An arab looking contented in natural self-carriage. His under neck is soft, his shoulders are enlightented. His tail is high and his topline slightly shortened but that is in the breeding of the Arab.

A Call for Conscious Horsemanship

It’s time to retire the romanticised notion of the “dancing horse.” Instead, let’s ask:

- Is the horse moving freely, or under duress?

- Is the posture functional, or forced?

- Is the training method kind or coercive?

- Does your horse have a voice, and are you listening?

- What is your true motivation, and does it truly promote the well-being of your horse?

- Who are you trying to impress, and is your horse paying too high a price?

FAQs

What is a “dancing horse”?

The term “dancing horse” is often used to describe horses performing rhythmic or stylised movements, either in cultural festivals (e.g. in India or Pakistan) or in competitive dressage. However, these movements are typically trained through coercive methods and do not reflect natural or joyful expression.

Are horses actually dancing in dressage competitions?

No. While dressage movements may appear synchronised with music, horses are responding to cues from the rider, not dancing of their own volition. The rhythm is imposed, not chosen, and the movements are often biomechanically unnatural or uncomfortable.

Why is “dancing” harmful to horses?

Forced movements, especially those that involve unnatural postures or repetitive strain, can lead to physical pain, emotional distress, and psychological shutdown. In both cultural and competitive contexts, horses are often trained through fear, discomfort, or learned helplessness.

How can spectators tell if a horse is suffering?

Signs of distress may include tension in the body, pinned ears, hollow backs, clenched jaws, or a lack of engagement in the eyes. Unfortunately, many of these signs are subtle and often misinterpreted as focus or discipline.

What’s the difference between your work and traditional dressage?

At Balance First, the focus is on the horse’s well-being - physically, mentally, and emotionally. Exercises are taught with the horse’s natural biomechanics in mind, encouraging relaxation, curiosity, and choice. The goal is not performance, but partnership.

Is it possible to teach advanced movements ethically?

Yes, but only when the horse is physically ready, emotionally willing, and mentally engaged. Movements should emerge from slowly building balance and strength, one step at a time, never asking the horse to do what he is not ready for and without force. Ethical training respects the horse’s individuality and avoids shortcuts that compromise welfare.

What is learned helplessness in horses?

Learned helplessness occurs when a horse is repeatedly exposed to aversive stimuli and eventually stops trying to escape or resist. This can look like obedience, but it’s actually emotional withdrawal and is a serious welfare concern.

How can I support ethical horsemanship?

Start by educating yourself on equine biomechanics, emotional signals, and humane training methods. Seek out trainers who prioritise the horse’s experience over visual results. And always ask: Is this movement helping the horse, or just impressing the crowd?

.JPG)