Table of Contents

- 1. The trim is key!

- 2. Keep their weight down

- 3. Watch for metabolic syndrome

- 4. Get the forage right

- 5. Limit what goes into their bucket

- 6. Use as much pain relief as needed, but as little as possible

- 7. Encourage or allow movement, but never force it

- 8. Abscesses are to be expected and are part of the healing process – don’t panic!

- FAQs

Laminitis in horses causes untold suffering for the animal and heartbreak for owners and caregivers.

When Marley first showed signs of discomfort, we didn’t yet realize we were facing one of the most challenging and misunderstood conditions in equine care. This is the story of how holistic support, biomechanical awareness, and patient listening helped him find his way back to balance.

One morning in July 2020, I found Marley standing on the muck heap. He was stuck. He must have been standing there for a long time. He had cleverly found the one spot where his feet felt the least uncomfortable and was reluctant to move.

Another morning, I found him lying on the deep bend in his stable, quietly whining, a bit like a dog. They say horses don’t cry out when they feel pain. I discovered that they do.

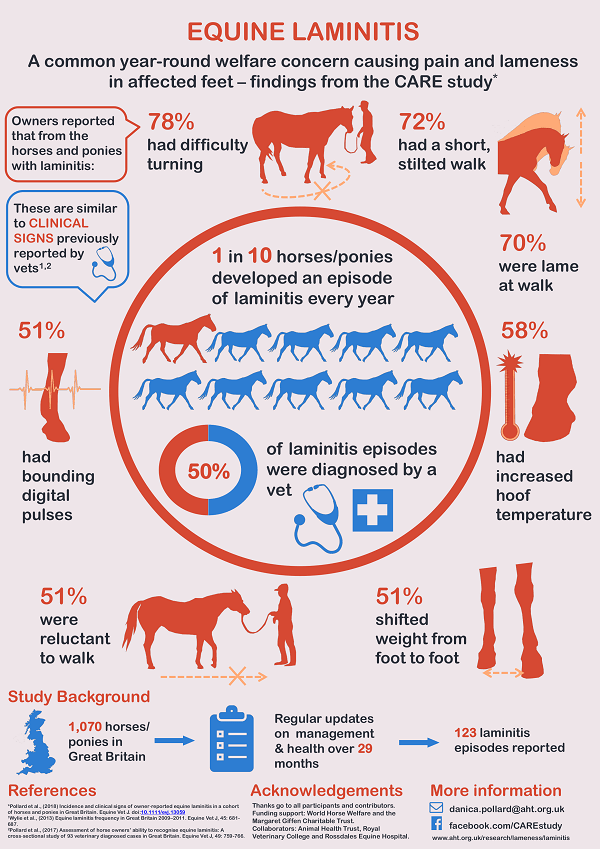

According to the Royal Veterinary College (RVC) website, more than 7% of all equine deaths are linked to laminitis, with many animals having to be euthanized. And 1 in 10 horses/ponies develops an episode of laminitis every year.

These are truly shocking statistics. This is an epidemic. Even with all the great information available about how to avoid laminitis, something is still going badly wrong.

We, as horse owners, need to take a long, hard look at the way we keep our horses to change this around.

Several years ago, when Marley was first found to be suffering with low-grade laminitis with a mild rotation of the pedal bone, the vet told me it was a mechanical laminitis – in other words, not a metabolic problem, but just that he had bad feet. The recommended treatment was rest on a soft surface.

What she didn’t tell me – or possibly didn’t know – is that I needed to find a trimmer who had the ability to trim his feet so that they could maintain a healthy shape.

In any case, I changed to a new trimmer who was very highly recommended for treating horses with laminitis. But still his feet were no better, and eventually his laminitis evolved into a rotation of his pedal bone and full-blown founder.

The vet strongly recommended I have heart bar shoes put on his previously shoeless feet.

I would now say without hesitation that there is a good chance that he would be dead now if I had taken that route.

Instead, I followed my instinct and took the incredibly difficult decision of going against the advice of the vet.

I want a horse with functioning hooves.

I knew I had to take massive action to get my beloved Marely through this.

So I took him to a trimmer that I knew could help him. It meant travelling him 30 minutes in the trailer every 6 weeks because she couldn’t come to my yard.

It was a long and incredibly difficult road, but it worked, and he is now striding out, his hooves are healthy, and he’s feeling fantastic!

For the first time, he is growing really nice, strong feet, and he’s feeling good in his body.

This blog is not intended to tell you what to do or what to believe. It is simply an account of my experience and what worked for me.

My precious horse suffered intensely and unnecessarily because of my mistakes.

And for me, it was one of the most traumatic experiences of my life.

These are the main points that I have taken away from the experience and would like to share in the hope that it helps other horse owners to avoid making the same mistakes that I did:

1. The trim is key!

When I had Marley vetted pre-purchase, I was advised not to buy him because of his poor foot conformation. But everything else about him was perfect, so I bought him anyway!

He was shod, and I was planning to keep him shod. But the farrier found it increasingly difficult to keep his toes back. His feet just wanted to grow forward and out, and spread.

So he recommended that I take him barefoot.

That went well for a while, even though his heels were under run and his feet spread out like dinner plates. But increasingly, he was developing long cracks in his feet and was gradually becoming unsound.

The walls would flare and split, the toes were very long, the heels were underrun

The walls would flare and split, the toes were very long, the heels were underrunI changed trimmers several times. When he finally foundered in 2020, I was using a trimmer who had been highly recommended. But I had still been having the same problem. His feet kept growing out, and the cracks would stubbornly not go away.

When I challenged the trimmer about it, she told me it would just take time and I had to be patient.

So I waited and waited until years went by, but things just didn’t get better.

All the time in the back of my mind was the voice of the vet saying that he had bad feet, so I sort of accepted that as just the way it is with Marley.

Eventually, when it got to crisis point, I knew I had to do something very different if I was going to save him.

I started travelling him to be trimmed by someone I felt hopeful would take a different approach.

She took his toes very hard back, at a 90-degree angle to the ground. This trim seemed quite dramatic to me. But she explained to me how it would enable the structures inside the hoof to realign themselves so that his hoof could start to heal.

She explained how his toes had been left far too long, and this creates a leverage on the hoof wall, which literally pulls the wall away from the laminae. As the laminae become damaged, the pedal bone drops, and the horse founders.

This is what is meant by mechanical laminitis.

And with a proper trim, it can be put right.

Don’t hesitate to change trimmers (or vet) if it’s not workingI am ashamed to say I put too much responsibility onto my trimmers in the past. And that part of my reason for not changing trimmers sooner is that I didn’t want to let them down. We spend a lot of time together, chatting. They become friends. And they believe in their own expertise, so why shouldn’t we?

Unfortunately, that is not necessarily in the best interests of the horse. We need to put the horse’s welfare first, at whatever personal discomfort to ourselves or the professionals we employ.

It’s against my nature. Not only do we feel we have to let someone down. But we also have to find a new trimmer who might do better – or might do worse!

Finding the right hoof care professional can be very difficult, and it can take time to see the changes in the horse’s foot.

This also applies to your vet, hay supplier, dentist, body worker, and anyone else who has access to your horse.

Learn as much as you can about hoof care, but know that everyone who teaches hoof care has their own opinion based on their own experience, and their opinion/experience will be dramatically different from others. So you will find experts who seem to be equally confident, competent, and passionate, who completely disagree with each other.

You just have to find what works for you and your horse, and that is your responsibility as the owner.

This one I personally found tedious. I didn’t get into horses to study their feet! But the old saying ‘no foot no horse’ is true, so we simply have to go there whether we like it or not.

We have to take the responsibility upon ourselvesI want my trimmer to tell me exactly what is going on. I want them to share their plan for the hoof and to want to educate me about what they are doing and why.

I want to be able to ask the difficult questions and get a clear answer.

For this, we need to ask questions so that we know what to look for in a good trim and we can recognise when things are starting to go wrong. There are many things to look for, and every horse is different. But a basic list is:

- The toes should not be allowed to grow too long

- The hoof should be well-balanced

- There should be no flare

- The soles should not be trimmed too thin

- The frog should be fat and healthy

- The heels should be upright, not underrun

- There should not be long, persistent cracks going up the wall, although when small pieces break off, this is a positive. It will give the trimmer a guide as to where the foot wants to be.

And if we are not satisfied, we need to take massive action and make a change.

2. Keep their weight down

Another mistake I made over the early years was allowing him to get a little too fat every year. When a horse is allowed to be overweight year-on-year, they can gradually develop metabolic syndrome. This is what happened to Marley.

It’s not as simple as just taking them off the field. All fields are not the same, and the exercise they get from moving around and grazing is essential for their well-being.

My field is small and seemed ideal for my good doers, because I used to rest it over winter and in summer the grass was always well-grazed and short.

But my horses got fat as soon as they went on there. This means that the wrong sort of grasses are flourishing in my field, and that’s a big risk. So until I can rectify that, I have them on a surfaced track around the outside of the field, and they are not going on the grass at all. This is working well for us.

Marley lost 50kg in less than 2 months when I took him off the field altogether, put him on the surfaced track, and put his hay nets around the track to make him search for it (they won’t move if the hay is in one spot). This is the best way to feed adlib. He can also pick at the hedge and the bits of grass around the track. So there is always something to find.

Weigh taping is also surprisingly helpful. It’s motivational to keep a record of their weight every few days or once a week to make sure things are on the right track.

Starving horses for weight loss is not a healthy option. It can be incredibly stressful and can make the weight problems worse long-term. Unfortunately, this approach is too often recommended by vets and can cause untold suffering.

3. Watch for metabolic syndrome

Marley is now very sensitive to grass. If you think your field is unhealthy or your horse might have metabolic syndrome, take it seriously BEFORE laminitis attacks. Ask your vet for a test. Google will give you a lot of information on it.

Metabolic syndrome is a common cause of laminitis in horsesSigns of metabolic syndrome to look out for are:

“Cresty neck” with firm fat along the nuchal ligament

Fat pads behind the shoulders, around the tail head, and above the eyes

These deposits often feel hard or lumpy, not soft like typical fat

Despite diet and exercise, the horse holds onto fat

Reduced energy, dullness, or reluctance to move

His laminitic stance, he would avoid putting weight on the toes of his front feet.

His laminitic stance, he would avoid putting weight on the toes of his front feet.4. Get the forage right

By far the biggest part of the horse’s food intake is (or should be) forage. When this is wrong, it can make a massive difference to your horse’s welfare.

I feed unsoaked low-energy meadow hay, as close to ad lib as possible.

Hay should be locally produced, good quality meadow (grass) hay, unsprayed, with a good mixture of grasses. Avoid ryegrass, ryegrass stalks, and straw, and have it tested for energy content.

The horse needs the valuable micronutrients found in a good-quality mixed hay in order to heal.

Soaking washes the nutrients away along with the sugars.

For a horse that is not on grass, sudden footiness is very likely to be down to a change in the sugar levels in your hay. And it can have a massive and immediate effect.

5. Limit what goes into their bucket

When he was very bad, I gave him no feed supplements at all. Nothing in his bucket but grass chaff, a gut balancer (prebiotic and probiotic), and Danillon. This is because their systems can become overloaded, and feed supplements can disrupt the gut biome.

Now he is stronger, I would not use a normal balancer because, without balancing the nutrients in your own forage, you risk making nutritional imbalances worse.

If your horse is only eating hay, it’s best to get your forage tested and get a diet plan so that you can balance the vitamins & minerals correctly.

6. Use as much pain relief as needed, but as little as possible

I prefer Danillon to Bute because it is less damaging to the gut. What happens in the gut also affects hoof health.

I would give Marley as much pain relief as he needed to be able to walk. On the very bad days, he was up to 5 sachets. But most of the time it was 2-4.

You need to be careful with this, though, and monitor your horse closely. We want the horse to be able to move calmly as much as possible so that the hooves can heal.

So my goal was to have him as comfortable as possible so that he could walk, but give him as little as possible to minimise the damage to his gut biome and avoid overloading his system.

7. Encourage or allow movement, but never force it

In order for a hoof to heal, it needs movement.

Horses kept on box rest are at a disadvantage because their feet are not functioning and are therefore not able to heal so well.

The movement needs to be controlled and gentle to avoid further damage to the hoof.

When Marley was very bad, he had access to a deep bed in a stable with the door open to the yard and track. This meant he did not have the stress of confinement (stress is a common cause of laminitis).

He could move when he felt comfortable enough, and he had the freedom to choose when to rest and lie down.

I would not advise doing this if there is a risk of your horse being bullied by others.

If he got stuck on the track, I would just gently walk him back to his stable and deep bed.

As soon as he was able to, and as much as possible, I would walk him in hand. At first, with his boots on and just around the yard. Then, around the arena on straight lines. Then, when he could cope, I took him on the lane.

It’s best to keep the goal in mind and go without boots as soon as possible. This way, the hooves will be better able to cope with different surfaces, and they will become stronger and heal more quickly.

I have found, though, that too much hand walking without boots is too much for his feet and sets him back, so getting the balance right with this takes careful judgment.

Now Marley and I are going for long walks on the tarmac road to keep healing and conditioning his feet.

8. Abscesses are to be expected and are part of the healing process – don’t panic!

Abscesses are one of the main reasons that so many laminitic horses are euthanized.

When the pedal bone drops and separates from the hoof wall, the laminae are damaged.

This creates dead material in the hoof that has to come out. When the hoof starts to heal and the pedal bone then starts to realign itself, the dead material is pushed out. This is when abscesses occur.

Abscesses are very painful and quite debilitating for horses. But usually they will burst in a few days.

The more the horse moves, the more the hoof can flex and the more quickly the dead material will be able to work its way out. A hoof that is not moving will take longer to heal from an abscess.

A shod hoof can’t move and flex like a bare hoof, and this also prolongs the pain and potential damage from an abscess.

Anti-inflammatories (Bute and Danilon) will slow down the progress of an abscess. We want them to burst as soon as possible to release the toxic material, but we also want to limit the horse’s pain. So ideally, we would not use them at all. But you would have to be pretty tough to do that!

I don’t know if it’s advisable, it’s just what worked for me, but I had a bit of a system going. I would give him a high dose of pain relief for the first few days, then take it away. I found that the abscess would burst the following day.

If you have a competent trimmer or vet who can make a hole in the hoof wall to relieve the pressure without taking away a lot of the foot, then this can be a good solution. But if they don't find the infection immediately, it can risk compromising the integrity of the foot and setting back the horse's recovery.

Seeing your horse suffering with an abscess can be distressing. And it can make us think it might be time to have them put to sleep. Or other people might make the suggestion.

Abscessing is likely to follow and episode of laminitis in horsesBut the horse’s demeanor tells a different story. Marley had several abscesses. He would lift his foot to show me where it hurt. But he didn’t seem terribly bothered by it, apart from the fact that he couldn’t use the foot and it was sore. It’s as if he knew that it was part of the healing process and that it would pass.

Once we understand this, it makes it much more bearable. Abscessing is a necessary process, and it shows that there are changes going on in the foot.

Sadly, it is common for owners to panic when there is a lot of abscessing and choose to have the horse put down. But it could be the very moment when things are about to turn around! This is what happened in our case.

Marley had a nasty abscess in a hind foot that I think had been quietly brewing for a long time. As soon as it burst, he turned a corner big-time, and a no more than a week later was striding out and walking confidently down the lane.

That was Christmas 2020, and we have not looked back since!

FAQs

What is laminitis in horses?

Laminitis is a painful and potentially life-threatening condition where the sensitive laminae inside the hoof become inflamed. It disrupts blood flow and can cause the hoof wall to separate from the bone.

What causes laminitis in horses?

Common causes include insulin dysregulation (as seen in Equine Metabolic Syndrome), high-sugar diets, stress, systemic illness, and mechanical overload. It’s often triggered by a combination of metabolic and environmental factors.

What are the early signs of laminitis in horses?

Early signs include shifting weight between feet, reluctance to move, heat in the hooves, increased digital pulse, and a stiff or short-strided gait. Horses may also lie down more frequently.

Can laminitis be cured?

Laminitis can be managed and, in some cases, reversed, especially if caught early. Recovery depends on the cause, severity, and quality of care. Holistic approaches that address diet, movement, and emotional stress can be highly effective.

Is laminitis in horses related to Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS)?

Yes. EMS is a major risk factor for laminitis. Horses with EMS often have insulin resistance, abnormal fat deposits, and a higher likelihood of developing laminitis, especially when exposed to high-sugar forage.